Inside Camp Cody - by C.A. Gustafson

Desert Winds Magazine - February 1995

The incidence of Camp Cody during World War I provided a most interesting and noteworthy chapter to the history of Deming, New Mexico. The United States declared war on Germany April 6, 1917. With a standing Army of only about 200,000, the nation made immediate plans to establish 32 training camps throughout the 48 states.

In May, the Army's examining board inspected the site of Camp Deming, which had encamped the National Guard during the Mexican crisis and closed only three months before. The village of Deming received word in June that it had been selected as one of the training sites; it would be named Camp Cody, after the famous buffalo hunter. The encampment would cover about 1,800 acres on the northwest fringe of the town.

Most of the 32 camps were located in the East and Southeast. Only four camps were situated in the far West: one in Washington, two In California and Camp Cody in New Mexico.

The tenure of Camp Cody could be categorized in three phases: the rise, July to November 1917; the crest, November 1917 to November 1918; and the decline, November 1918 to June 1919.

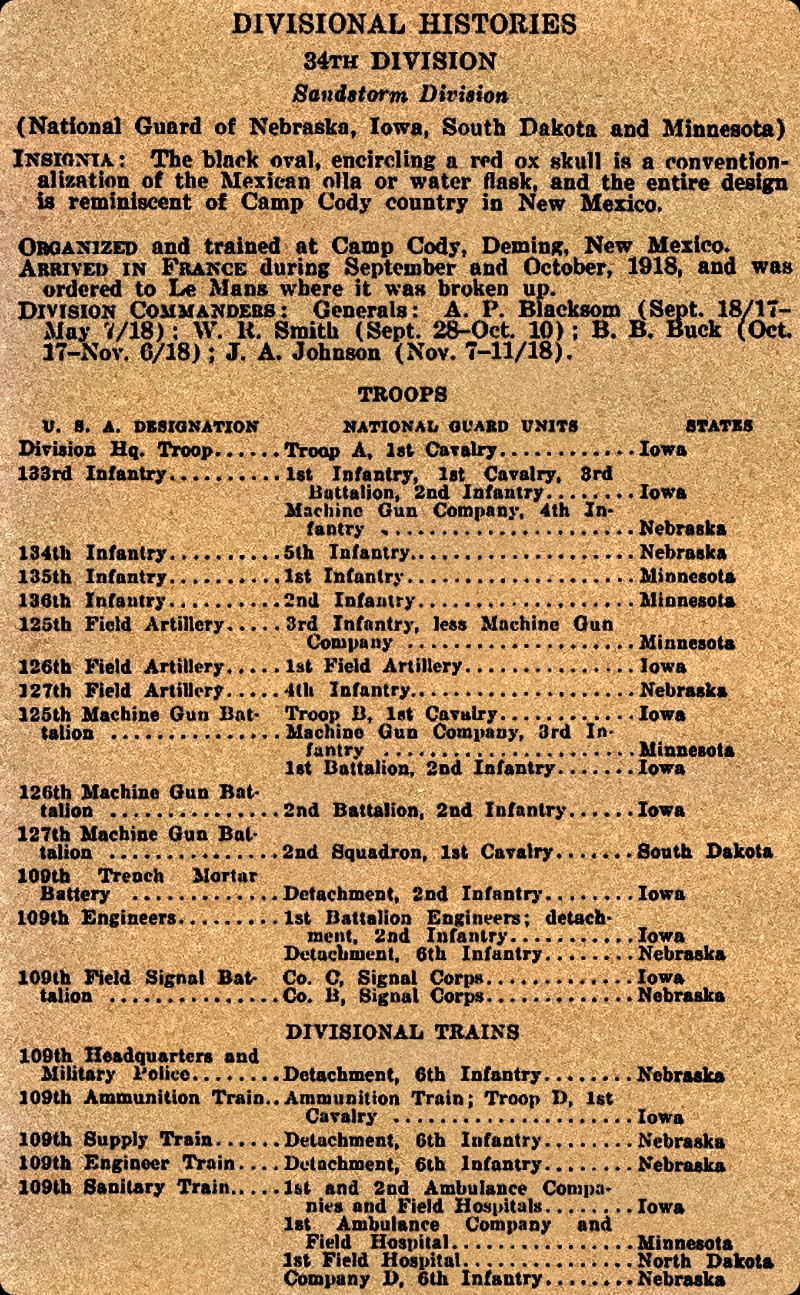

The oft-quoted figure of 30,000 soldiers at the local camp was actually for a short period. Construction began in July 1917, with 3,000 workmen employed at the height of activity. Early in October, the troops numbered around 10,000. Most of these were National Guardsmen from Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, and North and South Dakota. As construction neared completion in November, the soldier count increased to 22,000.

Early in 1918, Camp Cody contained about 25,000 troops. The influx of draftees during the mid months of the year increased the camp population to near its maximum. When the 34th Division shipped out to Fort Dix, N. J. to late summer, the base personnel dropped to about 3,000. Then another gradual buildup took place as the 97th Division began formation. At war's end in November, the troops numbered in the neighborhood of 9,000.

The first soldiers to arrive at Camp Cody found the transition from civilian life not to drastic. They were the National Guard from the aforementioned states. They had some basic military training. It was a different story for the draftees who arrived later. Most of them were apprehensive; some were frightened by the transition in their lives.

The inductees began arriving the latter part of 1917. Included were a group of Mennonites. They were named for Menno Simons, who founded the Protestant Christian sect in the 16th century. The group was opposed to the taking of oaths, military service and acceptance of public office.

The Mennonites who were shipped to Camp Cody were described as having scruples against fighting, working, washing and almost any activity - with the exception of eating. Some were wild looking individuals with long hair and full beards. With great reluctance, most of them finally donned uniforms and were assimilated into the military routine.

The drafted men arrived in batches of 500 from Camp Dodge (Iowa) and Camp Funston (Kansas). As they detrained, they were greeted by playing bands. After being formed in companies, they marched behind a band to their quarters, where tents were set up and a hot meal awaited. The route to their new homes was lined with "veterans" of a few weeks and sometimes days, ever ready to console and counsel the newcomers.

It was a difficult adjustment in the lives of those who were accustomed to the relative freedom of civilian life. Regimentation is wielded by the heavy hand of authority. In many cases, unfortunately, those vested with power choose to use it on their command as a weapon, rather than a tool.

It is estimated that 45,000 troops served at Camp Cody in its less than two-year existence. Each was the embodiment of a unique life chronicle.

What was life like within the confines of the Camp Cody cantonment? The streets were lined with pyramidal tents, eight men consigned to each. A Sibley stove, black in color and conical in shape, occupied the center. It burned wood, which was shipped into the camp. An electric light hung overhead. The mess halls and recreation facilities were contained in buildings. There was no paint, just new fresh lumber exposing its nakedness to the elements. Guards were everywhere, demanding a pass at every regimental boundary. Mountains of baled hay, piled 52 high, and were stacked along the tracks.

Inspectors constantly probed the area, insuring that it was kept spotlessly clean. Waste from the mess halls was burnt in incinerators. Details of men policed the camp areas every morning.

At 5:30 AM, a full band marched through the regiments, playing an inspiring march. Reveille followed; taps took place at 11 PM. Bugle calls sounded throughout the day, each signaling some activity. Sunday belonged to the soldiers, although they were accountable for periodic checks.

The remount station was located in the northern part of the base. It was equipped to handle 10,000 horses and mules. The site contained an immense loading platform, corrals, veterinary hospital and horse shoeing school. The facility covered 100 acres.

Entertainment was an important factor for the morale of the troops. An old reservoir that had been used to supply water to El Paso was converted into an outdoor amphitheater. The stage was 45 feet by 80 feet and benches were built to seat the entire division. It was dedicated in November 1917. The following April the Liberty Theatre opened and presented vaudeville, musical comedy, drama and feature films. The drop curtain displayed a scene from Ben Hur, painted by Rene Raoul from Kansas. Just off the base on the East end, a small community arose and was called Codyville. It contained a number of dance halls with names of "The Nebraska", "The Iowa" and "The Des Moines", obviously catering to the homesick element from those areas. There, the soldier could purchase soft drinks, listen to music and enter a roped area for a dance at 25 cents per.

Statistics of the day stated that a soldier sent to the battlefields of France had one chance in 30 to be killed and one in 500 that he would lose an arm or leg. Although Camp Cody was removed some 5,00-odd miles from the combat zone, it had a mortality factor of it own - lesser to be sure. The dubious distinction of the first to die at Cody belonged to Private Fess of Minnesota. He expired following an appendicitis operation in September 1917. Deaths at the Deming camp resulted from accidents, training mishaps, acts of nature (lightning caused a couple) and disease.

Records show that 67 died in the hospital the last four months of 1917. The following year, that number escalated to 426. Sixty percent of those deaths took place in the last three months of 1918. This, of course, was the critical period of the influenza epidemic. In November alone 194 were laid to rest in the final month of the war.

A modern sewage system for Camp Cody was approved in June 1918 at an estimated cost of a half million dollars. The following month, five ditching machines were at work preparing for its instillation. A giant septic tank was built on the East end of the camp. Its capacity was 2,500,000 gallons with the overflow running into the adjacent Mimbres River. The project was nearly complete at Armistice time when orders were issued to abandon the system. Located just off North Eight Street, the huge spillway is one of the few visible remains from the Camp Cody era.

World War 1 was publicized as the war to end all wars. It proved to be just another progressive phase in the art of mass murder. As long as mankind continues to harbor inner conflict, that dissension will be manifested in outer experience in the form of violence and war. When peach reigns within, serenity will prevail without.